One of the most persistent tropes in modern speculative fiction is the Hero’s Journey, or the Monomyth. The monomyth varies from telling to telling, and it can be found in a wide swath of modern media. The basic manifestation of the Hero’s Journey takes a protagonist from “normal life” into a fantastic setting where they are faced with conflict, personal struggle, and ultimately, they achieve triumph/glory over a villainous foe. In most tellings, a glorious return home completes the journey.

RPGs, from D&D to Exalted, use the Monomyth as their central narrative. White Wolf didn’t start with a substantial investment in the monomyth, and arguably the World of Darkness, and even moreso the Chronicles of Darkness, often explicitly subvert or at least de-emphasize the monomyth. It’s not hard to find player troupes that missed that memo and run heroic arcs with their Sabbat packs, Wraith circles, or throw themselves at the hero’s tale intrinsic to Changeling while ignoring the tragedy that’s clearly designed to subvert that narrative in the core text.

For all of the subversive ways the World and Chronicles of Darkness play with the Hero’s Journey, I’d never seen a game completely reject the validity of that story model until Beast the Primordial.

For all of the subversive ways the World and Chronicles of Darkness play with the Hero’s Journey, I’d never seen a game completely reject the validity of that story model until Beast the Primordial.

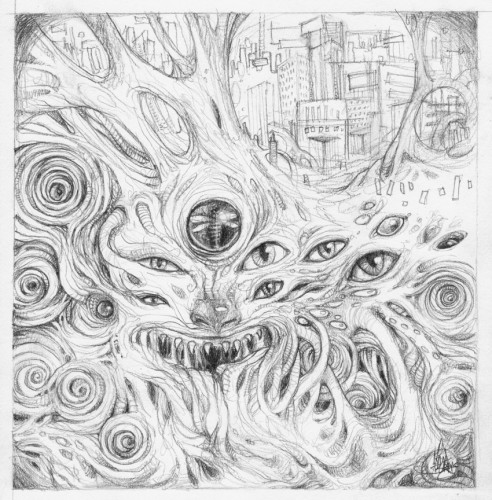

Beast devotes almost two and a half pages to the topic of how and why the game subverts/deconstructs the Monomyth. In Beast you play a monster of myth manifested within the soul of a human being. Beasts are driven to feast on human terror in uniquely personal ways. The primary antagonists of the game are “Heroes” who are driven by the same supernatural cosmology that creates Beasts to seek and destroy them.

It’s easy at first glance to think that this game is just a dark twist on the narratives common to our modern media, but the game does something much more compelling as you work through it. There is no monolithic enemy in Beast. Hero’s arise as stand alone phenomenon, every bit the cosmological constant Beasts are, and the culture of the Children (Beasts’ name for themselves), is incredibly loose and comes with no great political force to oppose. There is no Sabbat, no Technocratic Union, no Hierarchy, or corrupt guilds to stand against. The game emphasizes family, and the connection Beasts have with other supernatural creatures in the Chronicles of Darkness.

The fundamental conflict of Beast centers on the complicated task of finding your place in a world when that world finds everything you represent abhorrent. Heroes in Beast are clearly forged in the mold of the broken and corrupt heroes of Ancient Greece as opposed to the bright eyed perfection of classic Superman comics. They are deranged, driven, and while they may save a few humans from Beasts who have been pushed out of control by their hunger, it is a rare person who would say that is worth the collateral damage they cause.

Why is this framing so powerful? It seems due to the fact that the game forces the player to truly grapple with the experience of being the “other”. While that theme runs through many of White Wolf’s horror titles, Beast takes the metaphor further by casting the Beast’s greatest enemy as humanity itself. Heroes are twisted, deranged, and supernaturally powerful, but they are fundamentally human. It is the Beast who is not.

If you want to pick up Beast and give it a try one of the most important narrative considerations should be how comfortable you are with demonizing humanity. There is a sidebar in the Heroes chapter that asks, “What about the Heroes that listen to reason?”. The answer is that these heroes do exist, but they generally don’t hunt Beasts. The book continually states that the Heroes that should appear in a Beast game are the narcissistic, driven, cruel ones. I have seen a few people talk about having problems with this dynamic because it creates an unrelatable villain, and the book specifically states than Heroes should not be relatable enemies.

Heroes, at their core, are quintessentially human. So shouldn’t they be relatable? Modern storytelling has moved farther and farther in the direction of understandable antagonists, and messy flawed protagonists. Beast seems like an obvious attempt to dive directly into that dynamic, but when you step back and look at the game as a model that inverts a classic storytelling trope the problems with this lens become apparent.

Beasts are not good guys. You are not playing some gritty but relatable anti-hero. Despite the few words in the opening about how Beasts were outcasts, and “different” before their Devouring, this game is not some glorified revenge fantasy. The narrative that runs through the book emphasizes the constant struggle to keep existing while humanity continues to reject you, because you are fundamentally wrong. If you view this game through a lens where humanity is intrinsically good then a lot of the intended themes quickly fall apart, and I’ve seen this specific logical crisis in a great deal of the negative responses to the game.

Before playing this game you should really know your players, and you should spend some time making certain they are prepared to play true monsters in the night with none of the glorified romanticism that comes with games like Vampire or Changeling. You’re not flipping the tables so you can play a Beast anti-hero. There is no good guy in this story.

Before playing this game you should really know your players, and you should spend some time making certain they are prepared to play true monsters in the night with none of the glorified romanticism that comes with games like Vampire or Changeling. You’re not flipping the tables so you can play a Beast anti-hero. There is no good guy in this story.

Not every player will be able to get into this particular narrative headspace, and if even one or two players approaches this game with the wrong intent it could derail your whole chronicle. That said, approaching the game with this tilted perspective opens up new story possibilities. As a litmus test, if you dislike the writing of Thomas Ligotti due to the lack of a moral compass, even the inverted one present in more mainstream horror stories, this may not be the game for you. That particular form of nihilism is required to dive into the darker corners of Beast.

If the narrative darkness above sounds appealing there is still the question of game mechanics. I have seen consistent complaints that Beast is overpowered compared to the other games in the Chronicles of Darkness. After reading Beast I understand where that perception comes from. While the “powers” that Beasts purchase aren’t necessarily overwhelming (though they are powerful and a lot of fun) Beasts come with a barrage of innate abilities you don’t have to pay for. They have a special realm carved out of the Primordial Dream, they have the ability to transport there from a variety of places in the real world, they can buff other supernaturals they are allied with, and they automatically sense other supernaturals. There’s a system to create custom powers, which even though they must be purchased, is something you don’t often see, and these custom powers can become more unique when based off supernaturals a Beast is associated with.

Reading Beast, I felt like I was constantly stumbling over new powers, and it was a little overwhelming. However, I believe all of this power is important to further the fundamental themes of Beast. Unlike Mages, Werewolves, or Vampires, who might have driving goals, or grand schemes which their powers help them fulfill, Beasts are just trying to survive. More importantly, their power is a trap.

Satiety, which is the Beast’s supernatural resource, is complicated and dangerous. If you gorge yourself on the fear of your victims your inner Horror becomes fat and contented and you suffer penalties to your rolls. If you are starving, then your powers are buffed by your deep hunger, but your Horror (your Beastly soul) can easily run out of control and you are left with no resource to buff your powers. You may think this is a simple matter of maintaining balance between these two states, but as a primordial being you reject such equilibrium and grow uniquely vulnerable if you maintain the stasis between these two extremes for long.

If we look back at this system, and think about the themes of the game, it becomes immediately apparent that a Beast’s power reinforces the anxiety of their existence. Beasts have profound power, but every method of engaging with that power is toxic in a different way, and the more they leverage their supernatural strength, the more attention they draw from Heroes who want nothing more than to stand over their broken bodies. Even Wraith, which plays with a similar dynamic by having very shallow experience costs, but pairing PCs with a dark shadow that will abuse their drive for power, still comes with a set of enemies players can secure satisfying victories against.

When a Beast defeats a Hero all they gain is a brief rest before the next Hero finds them. As long as the Beast isn’t allowed to break out of that cycle, and Heroes are powerful enough to be a threat, no Beast can truly be overpowered, because their strength is a mockery more than an actual benefit.

Beast the Primordial is probably one of the most complex games in the of Darkness lines, both in terms of systems and due to its rejection of familiar narrative territory. The lack of a unified enemy, and the fundamental rejection of the Hero’s Journey are daring moves that align Beast with experimental narrative ventures like Dread or Bluebeard’s Bride as opposed to other games using the storyteller system. Game mechanics are fairly complex (satiety is no blood pool), and to be honest, I have a hard time imagining keeping track of all the different things I would be capable of as a player without a substantial cheat sheet.

Several sections of Beast drive the inverted Monomyth narrative in less than nuanced ways. This is most acute in areas that were re-written based on player critique during the kickstarter. Several players felt the game was too dark, that Beasts had no reason to exist, and that the relationship Heroes had with the Integrity stat was messy in toxic ways. To the dev’s credit they listened to the fans and made changes, but they did so very quickly and some of the text dealing with the themes introduced during the rewrite feel somewhat rushed. This is especially obvious in the reminders that only Heroes with low integrity hunt Beasts, though the fact that the devs made certain to leave high integrity Heroes in the world is significant, and I hope we get to hear more about them in the upcoming Beast Conquering Heroes.

Ultimately, Beast takes some profound risks, and in doing so creates a dynamic new corner of horror role-playing than many of us never knew existed. There are areas of the game that need some judicious application of the Golden Rule, such as the persistence of the “Beasts Teach Lessons” idea among the Children, without any coherent Beast society to perpetuate this culture. That said, some of my favorite White Wolf games have tapped into incredibly messy, yet fascinating narratives because they were willing to take risks, and they also required fairly liberal use of the Golden Rule to manage their rough edges, so Beast is in good company. Finding a large enough group of players ready to discard any heroic impulses and embrace the endlessly powerful anxiety of Beastly existence is a tall order (and may well resign Beast to my eternal bucket list alongside Promethean), but I do feel it’s a unique game that breaks new ground not just for the horror genre, but gaming more broadly and it’s well worth exploring.

Victor Kinzer has been roleplaying since he first picked up Vampire Dark Ages in high school. He nabbed it as soon as it was released (he might have been lusting after other Vampire books for a while at that point) and hasn’t looked back since. He role plays his way through the vast and treacherous waters of north Chicago, and is hacking away at the next great cyberpunk saga at http://redcircuitry.blogspot.com/. He is an occasional guest on Tempus Tenebrarum (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvNp2le5EGWW5jY0lQ9G39Q/feed), and is working to get in on the con game master circuit. During the rest of his life he works in Research Compliance IT, which might inform more of his World of Darkness storylines than he readily admits.

*Note, all opinions are the opinions of their respective Authors and may not represent the opinion of the Editor or any other Author of Keep On the Heathlands.