“The horror movie is innately conservative, even reactionary.” – Steven King

A World of Darkness dev introduced me to this quote on Facebook. He went on to explain the theory that the vast majority of horror is designed to make us afraid of the other, the thing that goes bump in the night, or stalks obscure corners of our world that we may one day be foolish enough to invade. This is not the conservatism of our modern politics, but a more fundamental use of the term rooted in the “maintenance of the status quo”. It is only by returning to normalcy that the beasts of the pit can be banished. There is a long history of these stories being used to reinforce societal norms, but there are as many examples of this small ‘c’ conservative format being used by creators who aren’t interested in maintaining any social status quo, but are fascinated by the human relationship to horror.

I’ve pondered this topic for a long time, and it strikes me, as role players, it’s worth understanding these themes in a meaningful way, because it helps us build the kinds of stories we want to tell at our tables. I’ve also found this model of horror illuminates why we are drawn to certain stories and not others. I think the best illustration of this dynamic is the relationship between Changeling: The Dreaming and Changeling: The Lost. I’m a long time fan of Changeling: The Dreaming, and when Changeling: The Lost came out for what is now known as the Chronicles of Darkness I went and dropped full MSRP on it without so much as cracking the cover. I had been jonesing for new Changeling content for years and it was with immeasurable excitement that I opened the book. After reading the text cover to cover I was in full blown Edition Warrior mode. I’ll spare you my barely more than a teenager histrionics, but suffice it to say, I was not a fan of the new game.

What really bothered me though is I WAS, kind of, a fan. There was so much in Changeling: The Lost that I loved and wanted in Dreaming. The kiths were flexible, the magic was more dynamic, the writing maintained a consistency of quality that unfortunately eluded Dreaming for most of the 90’s. I’ve talked with other Dreaming fans for years and hear this same sentiment over and over. The theme is consistently that Lost is a beautiful well done game but just . . . no and no one exactly knows why. Until recently I wasn’t able to find a satisfactory explanation for this feeling. I honestly believe the explanation lies in the Stephen King quote above.

What really bothered me though is I WAS, kind of, a fan. There was so much in Changeling: The Lost that I loved and wanted in Dreaming. The kiths were flexible, the magic was more dynamic, the writing maintained a consistency of quality that unfortunately eluded Dreaming for most of the 90’s. I’ve talked with other Dreaming fans for years and hear this same sentiment over and over. The theme is consistently that Lost is a beautiful well done game but just . . . no and no one exactly knows why. Until recently I wasn’t able to find a satisfactory explanation for this feeling. I honestly believe the explanation lies in the Stephen King quote above.

Changeling: The Lost is a quintessential example of the kind of horror King describes above. You play a creature abducted into the Hedge by Chthonic Fae horrors called The Gentry who is subjected to one trauma after another. When you return to the world, either through heroic escape, or your master growing bored and releasing you, your family doesn’t recognize you, and your entire existence is now a perpetual PTSD trigger reminding you that you barely survived. This is systematized to the point where using your own magic can trigger your morality trait, because it reminds you “you are wrong”. This creates stories of desperately wanting to re-establish the status quo of your previous life, but never pulling it off.

Even in the deepest, most interconnected motley of Changelings, there is always a background of “Yeah, we’ve lived through hell and worse together, but if I could go back to normal I’d ditch you all in a hot second and run screaming back to my wife/husband/children/etc”. I don’t know about the supplements, but the core book passes up no opportunity to remind you of this creeping sense of isolation, or that you are always desperately afraid of losing even this shadow of a normalcy should The Gentry return for you. One of the core messages of Lost is, “cherish the phantom normalcy you’ve been gifted because at any moment it could be stolen away. The Gentry remember”.

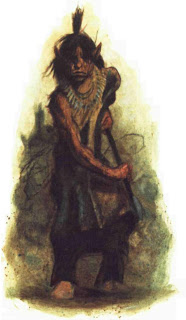

In contrast, Changeling: The Dreaming is a game that casts the status quo as the greatest horror in the game. You play a primordial creature born of human dreams. As with all World of Darkness games, you do indeed play a monster feeding on humanity in one way or another, but you are a monster because humanity dreamt you into being as a monster. If you make the world a bloody and brutal place it is not because something awful lives in the darkness, it is merely because humans BELIEVE something awful lives in the darkness, and would they believe or care if there were no status quo to shatter in the first place?

In contrast, Changeling: The Dreaming is a game that casts the status quo as the greatest horror in the game. You play a primordial creature born of human dreams. As with all World of Darkness games, you do indeed play a monster feeding on humanity in one way or another, but you are a monster because humanity dreamt you into being as a monster. If you make the world a bloody and brutal place it is not because something awful lives in the darkness, it is merely because humans BELIEVE something awful lives in the darkness, and would they believe or care if there were no status quo to shatter in the first place?

Even where the game slips into more Chthonic territory its core premise subverts the conservative nature of more mainstream horror. This is clear when you look at the Fomorians, who walked a path of darkness across the world in the earliest days of creation. The Fomorians now threaten to return to the world, but the fear of “the other” is always subverted by the fact that the darkest of Fae are still summoned by the dreams and fears of humanity, not the other way around. The Evanescence of dark glamour described in the Changeling 20th Anniversary edition originated with the atrocities of humanity, and even the myths of ancient times speak to the fears of humans at the mercy of a capricious world they did not yet understand. They do not speak of the Fomorians coming before the fear of the unknown.

Years after that first reading of Changeling: The Lost, the initial sense of “betrayal” I felt has passed and I see these games as possibly the perfect reflections of each other. In many ways this division assures that everyone has some corner of the Faerie they will love, which I deeply appreciate. If you approach these games with an awareness of these themes you can much more easily cast antagonists and scenarios that double down on, or explicitly subvert the core identities of the games.

Plot Seeds

In The Dreaming, the toxicity of the status quo of humanity, and the status quo of the Seelie court is hinted at throughout the game line, but is not often how the court is played. A story emphasizing those themes, with players who are Seelie opens a lot of narrative potential. Perhaps the most powerful saining magics of the Dark Ages aren’t as lost as everyone thinks, and if your players see the need to tear down oppressive feudal structures, but don’t want to be caught in the role of “the court of nightmares” then you could tell a story of great quests, and complex magics means to redefine the core identities of the courts, or perhaps even sain a new court altogether. There is nothing that compromises the status quo like redefining the basis of identity for your entire species.

On the other side of the Faerie divide Changelings in the Chronicles of Darkness who find themselves allied with a Beast may come to see the Beast’s hunting and the scars it leaves as a lesser form of the sins committed by the Gentry. Not all Beasts “teach their lessons” with equal elegance, and some make no attempt to teach lessons at all, seeking only to feed on the fear of mortals. The existence of Beasts, who exist to subvert the status quo, and Changelings, who are creatures uniquely driven to preserve it creates a dynamic where if you are aware of these themes you can tell truly brutal stories setting family member against family member. I would pity the poor Changeling who finds themselves allied with a Hero seeking to “purge the world of Horror”, but I could easily see how such an ill fated allegiance could emerge.

At the end of the day a solid foundation in genre awareness aids a storyteller running any game. When you find yourself guiding players through the darkest corners of humanity’s narrative canon look closely at what makes your players afraid, and tailor your setting to those fears. Knowing the deepest, broadest themes of any horror game makes it a lot easier to find exactly where those fears come from, and how to tap them.

“

“

Simon: Part of any good story is compelling antagonists. Changeling’s ultimate enemies, the autumn people, the people who disbelieve the fae out of existence, are a powerful metaphor for the destruction of culture. With that in mind, how do you go about creating autumn people that speak to that kind of horror while at the same time being sensitive to real world colonization experienced by the cultures reflected by the Gallain?

Simon: Part of any good story is compelling antagonists. Changeling’s ultimate enemies, the autumn people, the people who disbelieve the fae out of existence, are a powerful metaphor for the destruction of culture. With that in mind, how do you go about creating autumn people that speak to that kind of horror while at the same time being sensitive to real world colonization experienced by the cultures reflected by the Gallain?

Victor: I saw you comment online a few months ago about tweaks you were making to the Monsters in the book to remove some of the invisible bias that was present in previous editions of the game. Can you talk a little bit about how you approached this and in general how you approach making those kinds of revisions to RPGs with established fan bases who may be resistant to any changes in their favorite games?

Victor: I saw you comment online a few months ago about tweaks you were making to the Monsters in the book to remove some of the invisible bias that was present in previous editions of the game. Can you talk a little bit about how you approached this and in general how you approach making those kinds of revisions to RPGs with established fan bases who may be resistant to any changes in their favorite games?